First off, I apologize for the lack of updates. I’ve been sick on and off for the past few weeks and the task of writing a blog post seemed quite daunting at the time. Now, I am mostly recovered and there is so much to tell!

Now I must describe Bolivia’s most prominent annual celebration, Carnaval. Prior to arriving in Bolivia, I thought Carnaval was just a daylong holiday. Little did I know that Carnaval lasts a total of three months. Generally speaking, I’ve gathered that it draws from both Christian and indigenous myths and fables. Oruro, a mining town about three hours from Cochabamba, is known for hosting Bolivia’s most renowned Carnaval celebration, apparently rivaling the festivities in Rio de Janeiro. The city’s population is said to double or triple in size during Carnaval season.

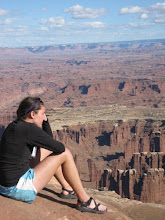

Though Carnaval celebrations, parades, and parties occur throughout the months of January and February, each city usually has one main day of festivities. In Oruro, this took place on the Saturday before Ash Wednesday, and luckily we had the opportunity to go. The bus ride was gorgeous: completely barren mountains, canyons, and valleys. We got in late Friday night, and the town was thoroughly geared up for the following day’s festivities. Wooden bleachers lined both sides of the main drag, streamers of every color flapped in the wind overhead, and thousands of people roamed the streets in merriment.

Most amazing was the energy of the Bolivians. Friday night’s music, dancing, and drinking lasted until 5am Saturday morning. Only three hours later, Saturday’s parade had begun. All in all, the succession of groups depicts the triumph of good over evil. Men, women, children, traditional bands and ornamented cars all proceeded down the main streets of Oruro for eight miles towards the church as an offering to the Virgin of Socavón, the city’s patron. Each group comes from a different location in Bolivia and offers a unique type of dance, dress, or music. Many dances tell stories of Bolivia’s history, such as the Morenadas, which represent the black slaves who worked in the mines. Some of these depictions appeared unethical from a “politically correct” point of view, since for the most part, minority Bolivian groups did not participate in the Carnaval festivities. Rather, upper class Bolivians were dressed as indigenous peoples and slaves. I was told that dancers pay upwards of $300 USD for their elaborate costumes, accompanying bands, and traveling expenses. Even purchasing a seat to watch the processions is fairly expensive. Thus, it seems somewhat like a holiday solely for the rich. Overall, however, it was an incredible insight to the traditions and folklore of Bolivian culture.

A final aspect of Carnaval that can’t be left out is the ongoing water war, which has become a massive part of the Carnaval tradition. Teenagers walk through the streets armed with ‘globos’ (water balloons) to throw at innocent pedestrians. While I had been hit and drenched several times during my first few weeks here, the water fights in Oruro were something else. Each time there was a gap in the parade, the spectators would engage in battle against the unfortunate souls across the street. Since soaking someone is clearly not enough, spray cans of foam are added to the mix. At times, this warfare was even more entertaining than the dancing, at least until I became the target. Getting a ‘globo’ to the face and foamed in the mouth and ears is no fun when you have no mechanism of defense. I am glad to say that now the mayhem has more or less subsided, and I no longer walk the streets in fear.

No comments:

Post a Comment